PHP or Type Safety: Pick any two

This is an abridged version of a talk I gave at the International PHP Conference in October.

PHP and type safety aren’t often used in the same sentence.

PHP is a very popular language that’s essentially the backend web development equivalent of a zero-entry swimming pool. It’s very easy to get your feet wet with PHP, and, in the last 25 years, millions of developers have.

Type safety is normally discussed in the context of much more formal languages like Haskell and StandardML — languages that offer, by design, protection against a whole bunch of problems but aren’t heavily used by the masses.

What exactly is type safety?

There are a number of different ways to define type safety. Academics normally say it’s a property of a given language: does that language’s compiler prohibit type errors in the execution of programs?

By this definition, PHP will never be type safe (PHP’s compiler hardly prohibits any type errors). But that definition also isn’t particularly useful to the majority of developers. For the purposes of this article, I’m going to define it this way:

Type safety measures the ability of available language tooling to help avoid type errors when running code in a production environment.

What’s a type error?

It's a program behaving badly, like this:

<?php

$a = "hello";

$a->foo();

In some languages (like Haskell and StandardML), type safety is pretty much guaranteed — the program won’t compile unless types are used correctly, and most modern compiled languages — Go, Swift and Rust for example — make it difficult to write programs with type errors.

How compiled languages prevent type errors

Compiled languages tend to be much stricter than interpreted languages like PHP, Python, and JavaScript. That strictness means that their compilers can produce efficient and reasonably type-safe output.

Most compilers check that both param and return types are provided. They then verify those types against what the given function produces. For example, Go's compiler analyses the code below and verifies that the function always returns an int. It's relatively easy for the compiler to verify that an int is always returned.

func Fibonacci(n int) int {

if n <= 1 {

return n

}

return Fibonacci(n-1) + Fibonacci(n-2)

}

Go's compiler stops you adding a type error — this code won’t compile:

func Fibonacci(n string) int {

// cannot convert 1 (type untyped number) to type string

// and many more errors

if n <= 1 {

return n

}

return Fibonacci(n-1) + Fibonacci(n-2)

}

These few strict rules have enabled Go's designers to construct a language where the type of every expression can be quickly inferred at compile time.

PHP and other interpreted languages don’t have those rules, and they don’t need types to be declared, either.

The equivalent PHP code for the fibonacci function looks like this:

function fibonacci(int $n) : int {

if ($n <= 1) {

return $n;

}

return fibonacci($n - 1) + fibonacci($n - 2);

}

fibonacci(10);

That same basic code runs just as well without the type annotations:

function fibonacci_untyped($n) {

if ($n <= 1) {

return $n;

}

return fibonacci_untyped($n - 1) + fibonacci_untyped($n - 2);

}

fibonacci_untyped(10);

Because interpreted code runs just fine without types, many codebases don’t have much type information.

Should you care if your codebase lacks types?

It depends.

If you’re working on a hobby project alone, you don’t need types. You might find them helpful, but they’re not necessary.

If you’re working on a professional project, and especially if you’re working on a professional project with other engineers, and super-especially if customers rely on that project to make money, you should use types wherever possible. The same applies if you’re creating a library designed to be used by others.

Adding types to interpreted code doesn’t improve its execution1, but it makes it much easier to spot mistakes, both now and in the future. Sort of like how driving at night with your headlights on doesn’t make the engine any more efficient, but it does help you avoid pedestrians.

If you really care about your code quality, you should not only see the value in types — you should want everything in your codebase to be typed. I’ll explain why, and I’ll also show you how you can enforce stricter type rules in PHP with Psalm, a static analysis tool I created.

Bugs creep in when types can’t be inferred

Here’s some code with a bug that goes undetected in other popular PHP static analysis tools:

function shouldTakeArrayOfStrings(array $arr) : void {

foreach ($arr as $a) {

echo strlen($a);

}

}

shouldTakeArrayOfStrings([new stdClass()]);

That’s because PHP's array type is a Swiss Army knife. It’s used in three distinct ways, and mistakes are easy.

Using one of Psalm’s supported docblock type annotations helps discover the bug:

<?php

/** @param array<int, string> $arr */

function shouldTakeArrayOfStrings(array $arr) : void {

foreach ($arr as $a) {

echo strlen($a);

}

}

shouldTakeArrayOfStrings([new stdClass()]);

Sometimes we need an even more specific annotation to find a bug:

/** @param array<int, string> $arr */

function getFirstOrDefault(array $arr, string $default) : string {

if ($arr) {

return $arr[0];

}

return $default;

}

// produces fatal error

getFirstOrDefault([1 => "hello"], "goodbye");

Using Psalm’s recently introduced list type – designed for arrays with sequentially-indexed values – can help us detect the bug, as any non-empty list must have an element at the zero offset:

<?php

/** @psalm-param list<string> $arr */

function getFirstOrDefault(array $arr, string $default) : string {

if ($arr) {

return $arr[0];

}

return $default;

}

getFirstOrDefault([1 => "hello"], "goodbye");

Adding type annotations helps us find bugs in PHP where they couldn't be seen previously. Psalm supports a whole lot more type annotations, enabling almost every data structure to be expressed as a docblock type.

We can take the argument further and say that the lack of a known type is its own issue, too. In fact, each of the "before" examples above also produce errors on Psalm’s type-safe mode, totallyTyped, but more on that later.

There are many other benefits of a well-typed codebase — adding more types doesn't just help us find bugs.

Other benefits of a type-safe codebase

Stress-free refactoring

I began to work on Psalm at Vimeo after a refactor went embarrassingly wrong. The stress induced when pushing larger refactors — namespacing many classes at once, moving methods, changing function signatures and the like — has probably shortened my life span by a few months.

In a type-safe codebase, refactoring is a mostly risk-free endeavour (and it can be cathartic for those of us who’ve suffered through the former experience).

Finding unused code

The larger the PHP codebase, the greater the likelihood that it has a bunch of unused code.

You’ll often have a scenario like this:

<?php // findUnusedCode

class A {

public function newMethod() : void {}

public function oldMethod() : void {}

}

/** @param A[] $arr */

function foo(array $arr, bool $use_new_method) : void {

foreach ($arr as $a) {

if ($use_new_method) {

$a->newMethod();

} else {

$a->oldMethod();

}

}

}

The feature rolls out, and then your code looks like this:

<?php // findUnusedCode

class A {

public function newMethod() : void {}

public function oldMethod() : void {}

}

/** @param A[] $arr */

function foo(array $arr) : void {

foreach ($arr as $a) {

$a->newMethod();

}

}

Sometimes you’ll forget to remove the old code — it happens, we’re human, and normally there’s no danger in keeping the unused code around.

But the unused code is like stacks of old newspaper in a hoarder’s apartment — it makes the codebase harder to navigate.

Adding types to your codebase and turning on Psalm’s unused code detection identifies code that isn’t being used. Psalm can even remove unused methods automatically.

Removing mystery from our codebase

I've listed the benefits, but how can we make sure Psalm can infer types for our entire codebase? By using totallyTyped mode!

totallyTyped mode

Psalm has a config flag called totallyTyped that makes Psalm complain any time it encounters an expression without a known type.

The experience is a little like writing in a compiled language, only there’s much less boilerplate, as Psalm’s typechecker can infer substantially more about your program than most compiled language type checkers.

“Help! I’m bombarded with errors!”

When running Psalm with totallyTyped turned on for the first time on a large codebase, you're bound to see all kinds of errors.

Your immediate reaction is likely to be “but my code works — fixing all these purported errors is a waste of my time”.

But wait! Psalm has a few ways to help you: automatic fixers and baseline files.

Psalm comes with a range of automatic fixers that help remedy a range of issues.

Psalm’s fixers can add, update and fix return types and add param types throughout your codebase:

<?php // fix

class C {

public static function foo($s) {

return strlen($s);

}

}

C::foo("hello");

Psalm can’t fix all the issues it can report, but with Psalm’s baseline functionality, you can grandfather in existing issues.

You can run Psalm with --set-baseline=your-baseline.xml to hide those errors on successive runs.

Doing this may seem counterintuitive — if those problems are real, why hide them — but your time is precious, and if you allow Psalm to find bugs in new code, pretty soon you’ll find yourself gradually improving the old code too.

At Vimeo, we've grandfathered in a bunch of method calls where we don't know what's being called — stuff like this:

function existingCode(array $arr) {

foreach ($arr as $a) {

$a->someMethod();

}

}

We allow this existing code in our codebase, but any new code that gets added like it results in a Psalm error.

function newCode(array $arr) {

foreach ($arr as $a) {

$a->someMethod();

^^^^^^^^^^

Cannot determine the type of object

}

}

We find this pattern very useful when working on a 13-year-old codebase. We can't fix everything at once, but we can ensure that new code is better than existing code, and the codebase tends towards having types everywhere.

Tracking type coverage at Vimeo

Every time you run Psalm it reports the percentage of types it can infer:

Psalm was able to infer types for 90.1827% of the codebase

This number represents the codebase’s type coverage, where 100% indicates a type-safe codebase.

We’ve used the techniques above to improve the type coverage of our codebase at Vimeo since introducing Psalm.

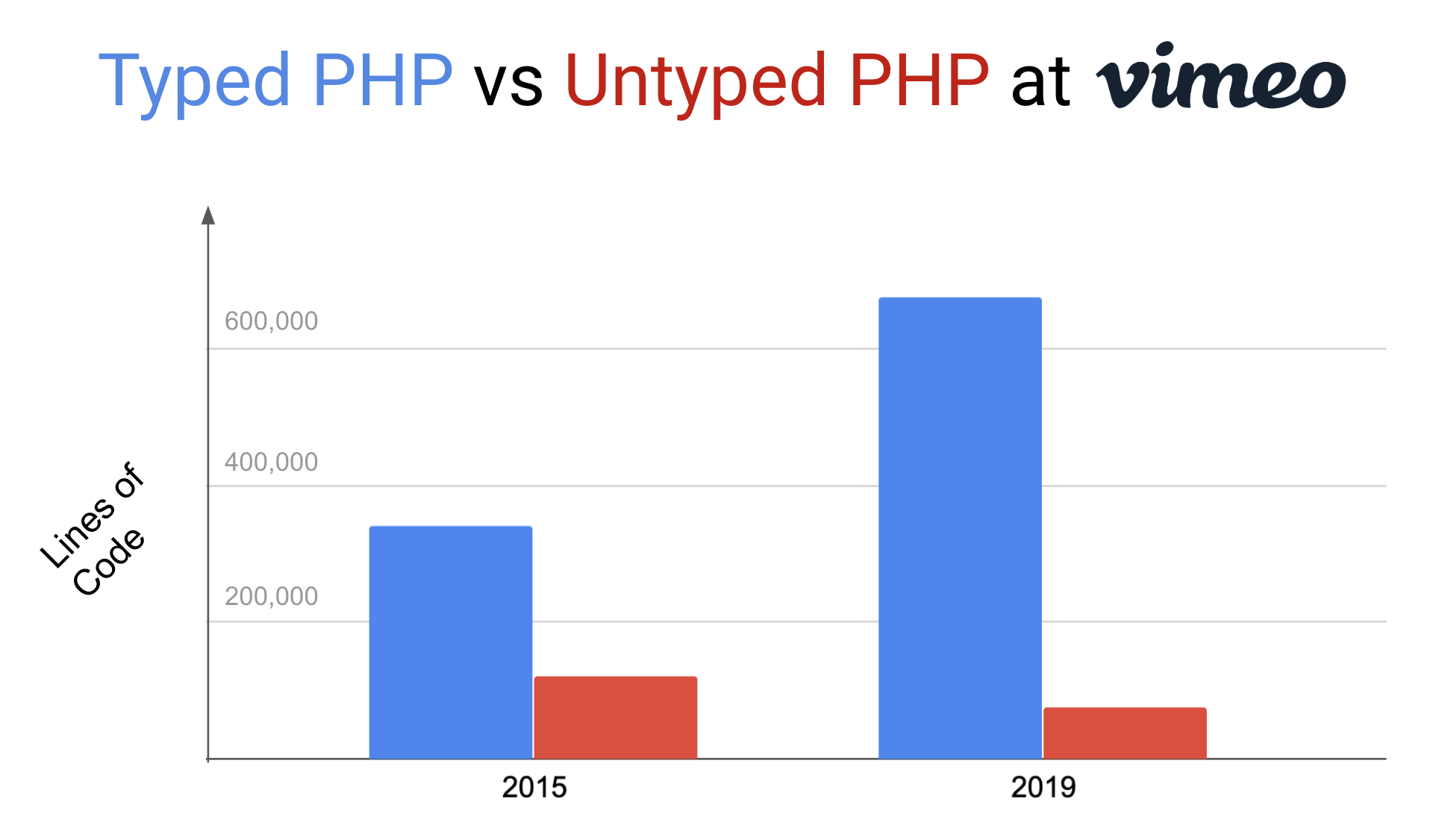

In 2015, before Psalm was introduced, about 74% of the codebase was well-typed. In 2019, about 90% of the codebase is. That increase has come even as we’ve roughly doubled the size of the codebase:

We’re still not done — I hope to have that untyped portion shrunk further in the next few months — but our ability to add new features without breaking existing ones has improved our communal sanity.

Tracking type coverage in public projects

Many public GitHub projects (Psalm included) display a small badge showing how much of the project’s code is covered by PHPUnit tests, because test coverage is a useful metric when trying to get an idea of a project’s code quality.

Hopefully, if you’ve got this far, you think type coverage is also important. To that end, I’ve created a service that allows you to display your project’s type coverage anywhere you want.

Psalm, PHPUnit and many other projects now display a type coverage badge in their READMEs.

You can generate your own by adding --shepherd to your CI Psalm command. Your badge will then be available at

https://shepherd.dev/github/{username}/{repo}/coverage.svg

This service is the beginning of an ongoing effort for Psalm to support open-source PHP projects hosted on GitHub.

Wrapping up

I've shown how types help you find bugs.

If people depend on your code, it should be well-typed (and you should use a static analysis tool to verify the types).

Psalm can help you ensure that your whole codebase has all necessary type declarations.

Now go forth and add types everywhere.

1 In a few rare circumstances it actually can, when running with Opcache in recent versions of PHP ↩